When Growth Leads to Protectionism: The Paradox Behind the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics

Public reactions to the Nobel Prize in Economics awarded earlier this month did not lack in quantity or conviction. The 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.” Many celebrated the choice of laureates and others criticized it for reinforcing the discipline's fixation on growth. Yet what the laureates’ work also reveals is the paradox of progress itself: the same forces of innovation that fuel growth also generate unemployment and inequality. Considering these negative impacts, the rise of protectionist policies in the U.S. can be understood as a reaction to the dynamics of innovation-driven growth as the laureates’ theory describes.

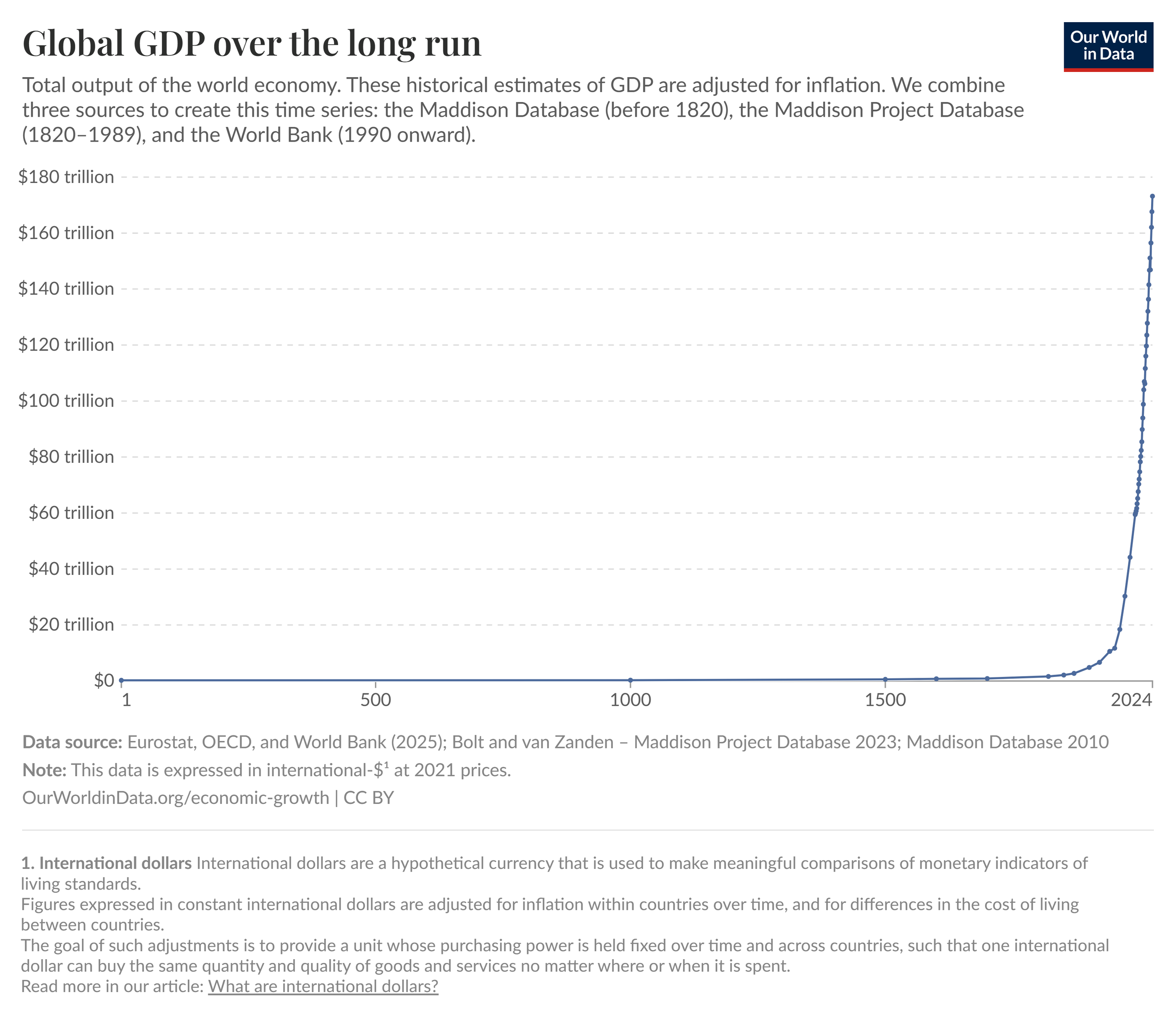

Half of the prize was awarded to Mokyr for his work identifying the conditions which have enabled the sustained economic growth seen since the Industrial Revolution, illustrated in the figure below. Mokyr identifies three key conditions that enabled sustained growth during the Industrial Revolution in the countries that experienced it most profoundly: knowledge of why things worked and how to make them work began to reinforce one another rather than remain separate; a new class of engineers emerged who could translate ideas into large-scale production; and societies grew more open to change, weakening the ability of vested interests to block progress.

Figure 1: Global GDP over the long run

The other half of the prize went to Aghion and Howitt, who built on Schumpeter's theory of "creative destruction." Schumpeter argued that economic growth is inherently disruptive, whereby every innovation, from steam engines to the internet to AI, replaces older technologies, firms and jobs. Aghion and Howitt formalize the theory with a mathematical model that identifies the mechanisms, incentives, and conditions through which creative destruction drives overall economic growth. The authors identify three key growth-promoting factors: first, that firms innovate when profits are expected; second, that innovation is strongest under moderate competition (monopolies are challenged but profits remain possible); and third, that sustained entry and exit of firms allows resources to go to the most productive firms.

In their Scientific Background to the Prize, the Nobel committee suggests that AI could accelerate GDP growth by democratizing theoretical and practical knowledge, one condition to which Mokyr attributes the acceleration of global economic growth. The committee then adds that AI could “lead to significant structural adjustments and many ‘losers'”, and thus “[s]upporting those who need help in changing jobs or occupation while not hindering the transition is an important challenge for policymakers.” The conclusion highlights the paradox that the same process that drives progress, innovation and creative destruction also produces disruption.

Aghion's comments in the wake of the prize have focused on criticizing protectionism and tariffs as obstacles to growth, stating: “I’m not welcoming the protectionist wave in the U.S.” Although the impact of Trump’s tariffs remains uncertain, it is evident that the protectionist policies stem in part from the economic fallout of decades of trade policies that fueled growth through creative destruction. In Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Schumpeter wrote: “The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop to such concerns as the U.S. Steel illustrate the same process of industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” (p. 83). Free trade policies led to the deindustrialization of the United States as American companies offshored production to take advantage of cheap labour and resources. Firms simply followed the factors of growth Aghion and Howitt identified: profits were expected to increase with lower costs, firms would become more competitive, and resources thus flowed to firms which offshored as they were most productive. Imposing tariffs, Trump’s protectionist policy, is a direct response to the creative destruction of U.S. firms displaced by global competition and offshoring. As announced on “Liberation Day,” Trump stated, “Jobs and factories will come roaring back.”

The critiques regarding protectionism from Aghion are particularly interesting in light of more recent work, such as Aghion et al. (2019), which finds a positive correlation between innovation and top income inequality across U.S. states and cities. Moreover, in their earlier theoretical work, Aghion and Howitt (1994) link the pace of creative destruction to higher unemployment, as increased innovation accelerates job turnover and displacement. These findings underscore the tension at the heart of growth, that the same innovation that fuels prosperity also deepens inequality and increases unemployment.

As the Nobel committee notes, “[s]ustained growth is clearly not equal to sustainable growth”. Aghion and Howitt’s work illustrates that creative destruction, while driving growth, also generates disruptions such as sectoral unemployment, regional economic decline, and increased inequality, which fuel political backlash. The process of creative destruction relies on a policy that fosters openness and competition. Yet these very disruptions fueled protectionist responses in the United States, such as Trump’s tariffs and “America First” trade agenda, which frame free trade and globalization for economic insecurity in deindustrialized regions. The paradox warrants further investigation: are such disruptions temporary adjustments that markets and transitional support can address, or do they signal enduring structural divides that entrench inequality and limit social mobility? The answer matters for policy. Without distinguishing between short and long-term disruptions, governments risk responding to transient shocks with permanent barriers or neglecting persistent inequalities in the belief that markets will self-correct.

References

Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Bergeaud, A., Blundell, R., & Hemous, D. (2019). Innovation and Top Income Inequality. The Review of Economic Studies, 86(1), 1-45. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy027

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1994, July 01). Growth and Unemployment. The Review of Economic Studies, 61(3), 477-494. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297900

The Economist. (2025, October 13). Joel Mokyr deserves his Nobel prize. The Economist. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/10/13/joel-mokyr-deserves-his-nobel-prize

Finbow, R. G. (2023). Populist Backlash and Trade Agreements in North America: The Prospects for Progressive Trade. Politics and Governance, 11(1), 237-248. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v11i1.6078

Henderson, D. R. (2025, October 13). The Nobel Nods at Economic Growth - WSJ. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.wsj.com/opinion/the-nobel-nods-at-economic-growth-d3260a73

Melber, A. (2025, April 2). Full Speech: Trump Announces Reciprocal Tariff, Baseline Tariff Plan | WSJ. YouTube. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6uFW0gHwXU

Roser, M., Rohenkohl, B., Arriagada, P., Hassell, J., Ritchie, H., & Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2025). Global GDP over the long run. Our World in Data. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-gdp-over-the-long-run

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. (2025, October 13). Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 - Press release - NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize. Retrieved October 28, 2025, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/press-release/

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. (2025, October 13). The Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 – Scientific Background. Nobel Prize. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/advanced-economicsciencesprize2025.pdf

Schumpeter, J. A. (1976). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Allen and Unwin.