Does Québec Belong in Canada’s Currency Union? An Optimal Currency Area Perspective

The question of whether distinct economic regions ought to share a common currency has long occupied a central and enduring place in international macroeconomics. Although in practice, political borders frequently determine monetary arrangements and organisation, economic theory has persistently emphasised that political sovereignty and monetary optimality do not necessarily coincide, nor do they invariably point in the same institutional direction or policy configuration.

This tension becomes particularly evident in contexts where political movements advocate independence while remaining deeply embedded within an existing economic, financial and institutional framework that has evolved over decades. Notably, Quebec, the sole francophone province within Canada with a tumultuous history of separatism, offers a particularly instructive case in this regard. Indeed, periodic calls for political independence have, at pivotal moments, been accompanied by proposals for monetary autonomy, including the creation of a distinct Quebec currency that would symbolise and operationalise sovereignty in the economic sphere.

Whether such a move would be economically coherent, however, cannot be answered through political reasoning and rhetoric alone. Put differently, political will may launch a currency union, yet economic logic ultimately decides its durability and feasibility. In this light, the Optimal Currency Area (“OCA”) theory provides the most systematic benchmark for judging whether a single currency is viable (though its criteria must still be weighed against fiscal, financial-stability and distributional considerations, all of which lie outside the OCA frame). In particular, it evaluates the conditions under which a shared currency maximises welfare by minimizing adjustment costs in the presence of economic shocks and structural disturbances. At the outset, Optimal Currency Area theory originated in the seminal contribution of Robert Mundell, whose contributions fundamentally altered the way economists conceptualise the relationship between geography, institutions and macroeconomic stabilization, for which he earned, in 1999, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Mundell formalised the idea that the desirability of a common currency depends not on national borders or political arrangements, but instead on the capacity of regions to adjust to asymmetric shocks without recourse to independent monetary policy. In Mundell’s framework, exchange rate flexibility functions as a shock-absorbing mechanism when regions face divergent economic conditions, allowing relative prices to adjust and resources to be reallocated in response to localised disturbances. However, it is noteworthy that Mundell also emphasised that exchange rate flexibility is not an end in itself. In effect, when alternative adjustment mechanisms are present, the welfare gains from a common currency, including lower transaction costs, the elimination of exchange rate uncertainty, enhanced price transparency and deeper market integration, may outweigh the loss of monetary autonomy. As such, the exchange rate, in this view, is only one instrument among many, and its usefulness depends critically on the institutional and economic environment in which it operates.

Mundell receiving the Nobel Prize in Economics from Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf, 1999.

Subsequent contributions steadily refined and expanded this framework by identifying a series of criteria that characterise an optimal currency area. Robert McKinnon emphasised the importance of economic openness and asserted that highly open economies derive limited benefits from exchange rate flexibility, since domestic prices are closely tied to international prices and exchange rate movements quickly pass through to domestic inflation. In such contexts, monetary independence offers little insulation from external shocks. Peter Kenen, in turn, highlighted the role of production diversification and argued that economies with a broad, diversified production base are less vulnerable to sector-specific shocks and therefore require fewer nominal adjustments to maintain macroeconomic stability. Over time, these insights were synthesised into a more comprehensive framework encompassing labour mobility, capital mobility, price and wage flexibility, fiscal transfer mechanisms and the symmetry of business cycles across regions. All in all, these criteria provide a structured framework for evaluating whether the benefits of monetary integration outweigh the costs of relinquishing monetary sovereignty.

Importantly, political independence does not mechanically imply the desirability of monetary separation, a point that is often overlooked in public discourse. Indeed, historical experience provides numerous examples of sovereign states that have voluntarily forwent monetary autonomy, either through formal currency unions, a notable example of which being the adoption of the Euro in light of the formation of the European Union (EU), or through unilateral adoption of a foreign currency, when doing so was perceived to enhance credibility, stability or economic efficiency. The central question, therefore, is not whether Quebec could issue its own currency, since the technical capacity to do so is indubitably and incontrovertibly present. Rather, the relevant and most acute question is whether such a choice would enhance macroeconomic stability and welfare relative to remaining within the established Canadian monetary union headed by the Bank of Canada (BoC). This distinction has been explicitly recognised in the Canadian context. Analytical work conducted during the 1990s, in anticipation of potential Quebec secession, emphasised that monetary arrangements should be evaluated independently of constitutional outcomes and political preferences. In practical terms, an independent Quebec would face a range of currency options, including unilateral use of the Canadian dollar, participation in a negotiated currency union, or the creation of a new currency operating under either a floating or pegged regime. Each of these options entails significant trade-offs in terms of credibility, flexibility and economic integration, trade-offs that OCA theory is uniquely suited to evaluate in a systematic manner.

Headquarters of the Bank of Canada, Ottawa.

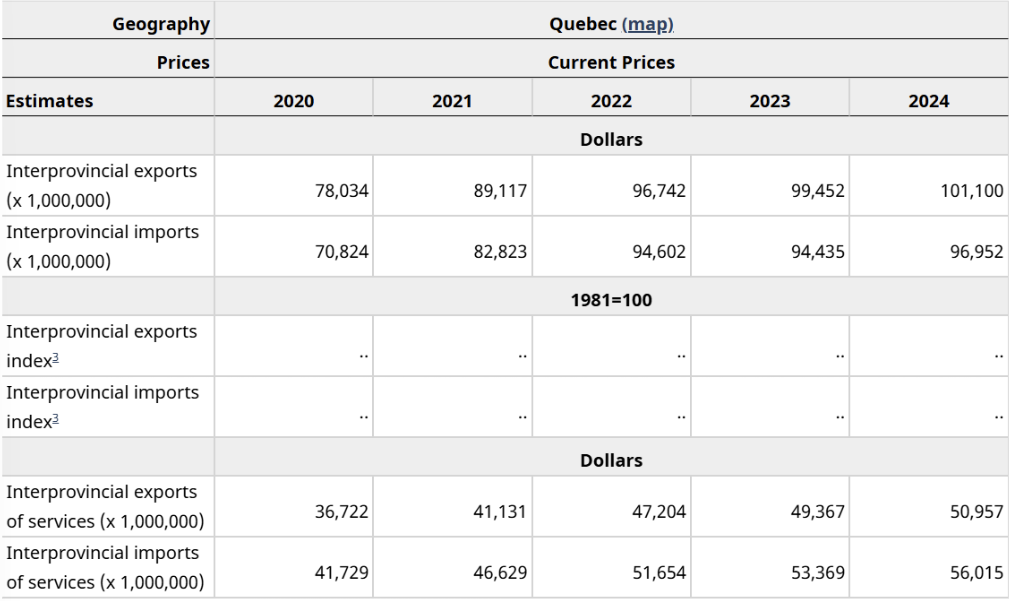

Notably, one of the most potent arguments in favour of a shared currency arises from the degree of trade integration between regions. Indeed, high internal trade intensity magnifies the costs associated with exchange rate volatility while simultaneously increasing the benefits associated with a common medium of exchange. Empirically, Quebec is deeply integrated into the Canadian economic space. In different terms, interprovincial trade accounts for a substantial share of Quebec’s total trade and exceeds its trade with any single foreign partner, including the United States, which remains Canada’s dominant and closest external trading partner. In light of this, the introduction of a Quebec-specific currency would therefore impose exchange rate risk on a large volume of existing transactions that currently take place within a stable, unified monetary framework. Such a development would raise transaction costs, complicate price setting and introduce uncertainty into supply chains that have been structured around a common currency for decades.

Moreover, the relationship between trade and currency choice is not merely static. Frankel and Rose demonstrate that currency unions tend to increase trade integration over time, thereby making regions more optimal currency areas ex post than they were ex ante. This insight is of particular relevance in the Quebec context. Specifically, the province’s prolonged participation in the Canadian monetary union has not merely coincided with economic integration; it has actively contributed to it. The Canadian Dollar, the nation’s common currency, has facilitated the development of dense commercial linkages, integrated production networks and interprovincial supply chains that would be costly to unwind. In this sense, the Canadian dollar is not simply a neutral policy instrument but an institutional complement to Quebec’s economic integration within Canada, thereby reinforcing the very conditions that render monetary separation economically unattractive.

Between 2020 and 2024, Quebec has consistently engaged in interprovincial trade with other Canadian provinces, amounting to well over one hundred billion dollars annually.

Source: Statistics Canada

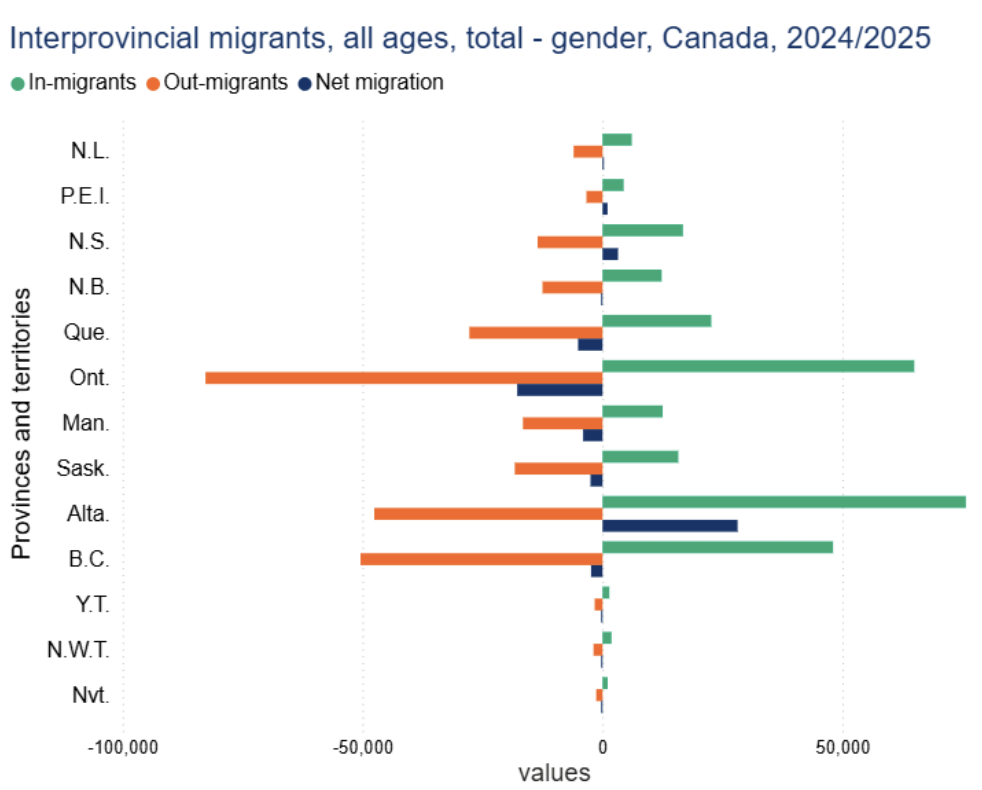

In the absence of exchange rate flexibility, labour and capital mobility play a central role in facilitating internal adjustment to economic shocks. On this account, Canada performs relatively well on both dimensions, as interprovincial migration responds meaningfully to regional labour market conditions, with workers relocating toward provinces exhibiting stronger employment prospects and higher real wages. While linguistic, cultural and regulatory factors may reduce mobility between Quebec and other provinces relative to mobility within anglophone Canada, empirical evidence indicates that labour flows remain substantial by international standards. In comparative perspective, labour mobility within Canada far exceeds that observed across sovereign states in the euro area, where linguistic, legal and institutional barriers significantly impede adjustment and contribute to persistent regional unemployment differentials. Further to this, capital mobility is even more pronounced, as Quebec firms operate within an integrated national financial system, with unrestricted access to Canadian capital markets, banking institutions and payment systems. In this light, monetary separation would likely disrupt this integration, raise financing costs, complicate cross-border investment within Canada and increase vulnerability during periods of economic stress.

Interprovincial migration in Canada (2024-2025)

Source: Statistics Canada

The extent to which regions experience similar economic shocks constitutes a core determinant of currency union viability. If Quebec were persistently subject to idiosyncratic disturbances distinct from those affecting the rest of Canada, the case for monetary autonomy would be considerably stronger. However, available evidence suggests that Quebec’s business cycle is closely synchronised with the Canadian aggregate. Studies of regional economic performance in Canada reveal substantial co-movement across provinces, particularly in response to national demand fluctuations and monetary policy shocks transmitted through a unified financial system. Furthermore, although Quebec’s industrial structure, characterised by a considerable manufacturing base and a large hydroelectric sector, introduces some sectoral specificity, these differences have not historically generated large or persistent asymmetric shocks. In practice, Quebec’s economic fluctuations more closely resemble those of Ontario and the broader Canadian economy than the divergences observed between core and peripheral economies within the euro zone, where structural differences and limited adjustment mechanisms have produced prolonged imbalances.

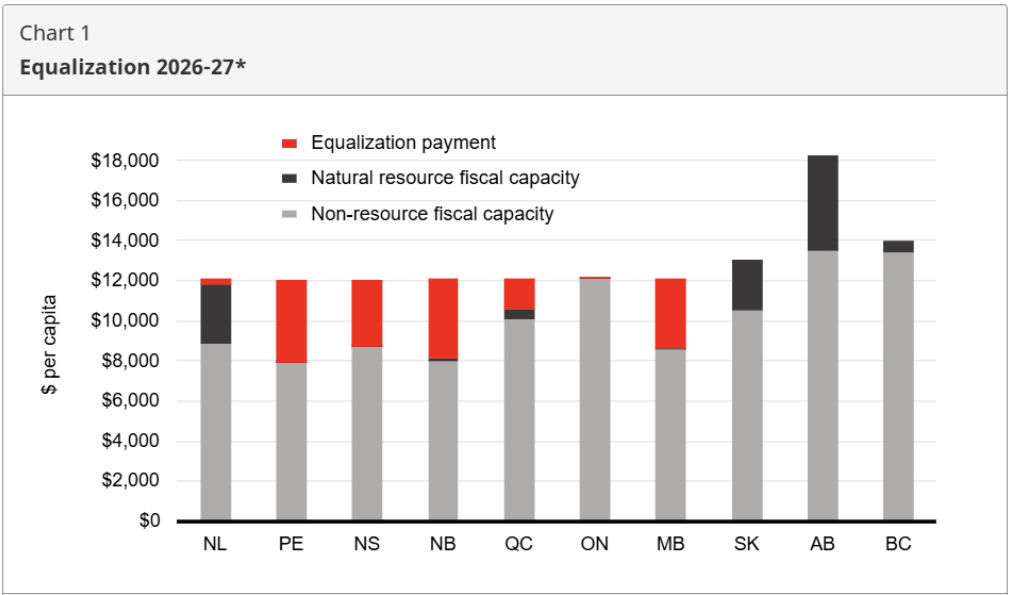

Planned Federal Equalization Payments for 2026-2027

Source : Statistics Canada

One of the most decisive arguments in favour of the Canadian monetary union lies in the robust fiscal transfer mechanisms. Federal equalisation payments and automatic stabilisers redistribute income across provinces in response to cyclical and structural disparities (thus functioning as powerful shock absorbers that mitigate regional volatility). Moreover, theoretical and empirical work on fiscal federalism demonstrates that such mechanisms substantially smooth regional consumption and reduce the welfare costs associated with asymmetric shocks in currency unions. As such, the contrast with the euro area is instructive. The absence of a centralised fiscal authority capable of large-scale transfers has been widely identified as a structural weakness of the European monetary union (which exacerbates regional divergences during periods of crisis and forces adjustment to occur through painful internal devaluations ) . Canada, by contrast, exhibits precisely the form of fiscal integration that OCA theory identifies as a prerequisite for a stable and efficient currency union. Quebec is thus a net beneficiary of these arrangements, implying that monetary separation would entail not only exchange rate risk, but also the loss of an important stabilization mechanism.

Advocates of the establishment of a Quebec currency often emphasise the symbolic and practical appeal of monetary sovereignty through the argument that control over interest rates and exchange policy would enhance macroeconomic flexibility and policy autonomy. Yet, the empirical literature casts doubt on the effectiveness of such autonomy for small, open economies. Indeed, many countries endowed with formal monetary independence exhibit a pronounced reluctance to allow their exchange rates to fluctuate freely, intervening heavily in foreign exchange markets due to concerns about inflation pass-through, capital flight, balance sheet effects and financial instability, a phenomenon commonly described as “fear of floating”. Moreover, the credibility of a newly created currency would be uncertain, particularly in the absence of an established track record. Establishing a lender of last resort, accumulating foreign exchange reserves and maintaining financial stability during the transition would pose significant challenges. Comparative analyses of secessionist cases, a notable example of which is Scotland, suggest that currency choice constitutes one of the most complex and economically consequential dimensions of independence, with no feasible, costless option available and significant trade-offs between credibility and flexibility.

All in all, the evidence indicates that Canada constitutes a remarkably strong currency area that includes Quebec. Indeed, high trade integration, substantial labour and capital mobility, synchronised business cycles and, most decisively, robust fiscal risk sharing mechanisms collectively imply that the economic costs of monetary separation would likely exceed the benefits associated with independent monetary policy in the context of an independent state of Quebec. Crucially, it warrants emphasis that this conclusion does not negate the legitimacy of political aspirations for sovereignty, but rather simply clarifies the economic constraints within which such aspirations must be evaluated and analysed. In particular, it illuminates the trade-offs that accompany institutional and political choices and highlights the conditions under which those choices are likely to enhance or undermine economic welfare. In other words, Optimal Currency Area theory does not, nor can it, adjudicate salient and integral questions pertaining to identity, culture or political legitimacy. Accordingly, in the case of Quebec, the balance of evidence suggests that while monetary separation and independence would represent a significant departure from economic optimality as defined by contemporary macroeconomic theory, political independence may remain a legitimate and pertinent debate based on cultural, historical, identitarian or constitutional grounds.

Sources

Blanchard, Olivier J., and Lawrence F. Katz. “Regional Evolutions.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 23, no. 1 (1992): 1–75.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/1992/01/1992a_bpea_blanchard_katz_hall_eichengreen.pdf .

Brenner, Reuven. “Financial Options for a Country Waiting for a Divorce.” Faculty of Management Working Paper. McGill University, 1994.

https://www.mcgill.ca/desautels/files/desautels/channels/attach/financial-options-for-a-country-waiting-for-a-divorce-reuven-brenner.pdf .

Calvo, Guillermo A., and Carmen M. Reinhart. “Fear of Floating.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117, no. 2 (2002): 379–408.

http://papers.nber.org/papers/w7993 .

De Grauwe, Paul. Economics of Monetary Union. 9th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Department of Finance Canada. “Equalization Program.” Government of Canada, 2024.

https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/federal-transfers/equalization.html .

Frankel, Jeffrey A., and Andrew K. Rose. “The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria.” Economic Journal 108, no. 449 (1998): 1009–1025.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2565665 .

Institute for Government (UK). Currency Options for an Independent Scotland. London: Institute for Government, 2019.

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/scotland-currency .

Karaguesian, Julian V. “Europe: An Optimum Currency Area in Search of a Common Currency.” MA thesis, McGill University, 1991.

Kenen, Peter B. “The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas: An Eclectic View.” In Essays in International Economics, 163–182. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbcd28k.

Laidler, David, and William Robson. Two Nations, One Money? Canada’s Monetary System Following a Quebec Secession. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, 1991.

https://cdhowe.org/publication/two-nations-one-money-canadas-monetary-system-following-quebec-seccession/ .

Lévesque, Fanny. “Pas de monnaie québécoise avant un minimum de 10 ans.” La Presse, November 15, 2025.

https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/politique/2025-11-15/quebec-independant/pas-de-monnaie-quebecoise-avant-un-minimum-de-10-ans.php.

McKinnon, Ronald I. “Optimum Currency Areas.” American Economic Review 53, no. 4 (1963): 717–725.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1811021.

Mundell, Robert A. “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.” American Economic Review 51, no. 4 (1961): 657–665.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1812792 .

Robson, William B. P. Change for a Buck: The Canadian Dollar after Quebec Secession. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, 1991. https://cdhowe.org/publication/change-buck-canadian-dollar-after-quebec-secession/.

Sala-i-Martin, Xavier, and Jeffrey D. Sachs. “Fiscal Federalism and Optimum Currency Areas: Evidence for Europe from the United States.” NBER Working Paper No. 3855. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1991.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w3855 .

Sørensen, Bent E., and Oved Yosha. “International Risk Sharing and European Monetary Unification.” Journal of International Economics 45, no. 2 (1998): 211–238.

https://www.uh.edu/~bsorense/jiepublished.pdf .

Statistics Canada. “Interprovincial and International Trade Flows, Annual.” Table 12-10-0101-01. Government of Canada.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1210010101 .

Statistics Canada. “Interprovincial Migration Indicators.” Government of Canada, 2022.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2022017-eng.htm .

Tavlas, George S. “The ‘New’ Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.” World Economy 16, no. 6 (1993): 663–685.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.1993.tb00189.x.