Eurobonds: How Europe can reassert its sovereignty and bring back growth

The last few weeks have shown that Canada and Europe can no longer rely on the United States for defence. Rather, the United States has morphed into a threat under Republican control. As European troops deploy to Greenland to reaffirm its sovereignty, policymakers in Brussels must consider strategies to ensure European sovereignty and long-term economic growth. Deepening the burgeoning market for joint-issued EU debt to finance defence, infrastructure, and other public investment is necessary to continue supporting Ukraine and to face off the American threat.

In December, the EU agreed to a €90 billion loan to Kyiv financed through joint borrowing on capital markets backed by the EU budget. However, eurosceptical Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia were exempted from the policy. The loan will cost an estimated €3 billion in annual interest payments. This rare show of European fiscal solidarity was precipitated by NextGenerationEU, Europe’s COVID recovery plan, which allows for up to €700 billion of common borrowing.

NextGenerationEU, which essentially allowed for the issuance of Eurobonds, was highly controversial. The notoriously frugal Dutch and their fiscally conservative peers dragged their feet, not wishing to back any program that, in their view, rewarded Europe’s more indebted southern and eastern nations at the expense of net-creditor countries like the Netherlands and Germany. Eventually, reluctant countries capitulated, recognizing that COVID and its accompanying economic shock posed a grave threat to all of Europe.

As Spain’s then foreign minister Arancha González put it, “We are in this EU boat together. We hit an unexpected iceberg. We all share the same risk. No time for discussions about first- and second-class tickets … History will hold us responsible for what we do now.”

González’s emotional appeal makes a lot of economic sense, too. Issuing common debt expands Europe’s collective fiscal capacity by reducing borrowing costs through multiple mechanisms. A deep and liquid Eurobond market would attain a safe asset liquidity premium, pushing down yields. As this market matures, it would develop the attributes of other fixed-income markets—a deeper yield curve (i.e. liquidity at every maturity), a futures market, and a robust repo market—further pushing down borrowing costs. All European countries would be able to borrow at rates close to the German Bund rate.

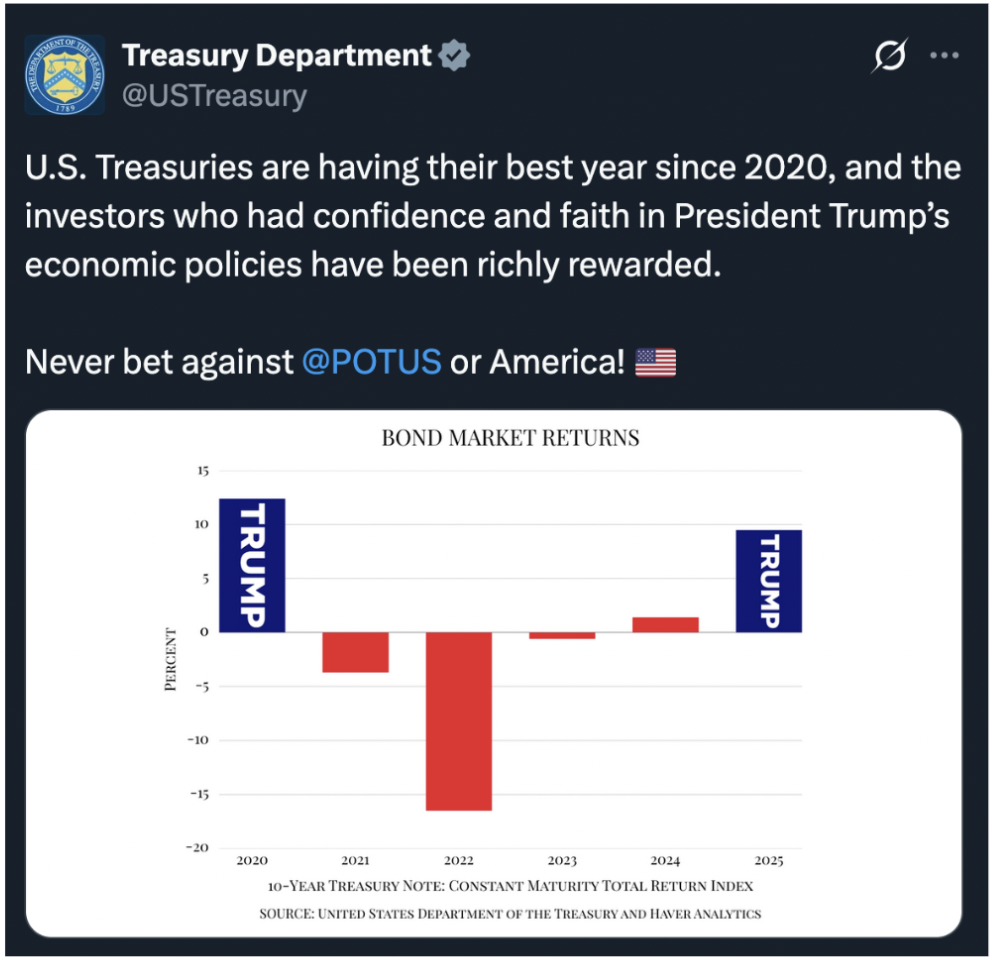

Along with security guarantees, the Americans used to provide Europe (and the rest of the world) with a perfectly safe investment vehicle: the Treasury. The US bond market, traditionally viewed as liquid and safe, underpins the global financial system. But with Trump’s erratic trade policies and the declining credibility of US institutions—not to mention the astounding economic illiteracy of the current White House—some investors are looking to rebalance away from the American dollar.

The markets for the various bonds issued by European governments are not large enough to provide the stability investors demand. The depth of the market matters for liquidity and for flexibility: institutional investors need to be able to make large trades without affecting prices. Further, the current European sovereign debt market is fragmented: German, Italian, French, and Spanish bonds have different credit risks, primary dealer networks, and legal and regulatory frameworks.

The institutionalization of a common European bond market and policy coordination are necessary to reassure investors and lower borrowing costs for European governments. Europe’s lack of fiscal policy coordination is harmful. For example, Brussels still hasn’t decided whether to roll over or repay the NextGenerationEU bonds. Because of this lack of policy clarity, “EU-bonds are not treated by investors as sovereign bonds, but rather as supranationals, and are not included in sovereign bond indices, reducing the demand and keeping their yields higher than otherwise,” according to economists Olivier Blanchard and Ángel Ubide.

European fiscal solidarity has been lacking in the past, and with shameful consequences. Southern Europe basically had a lost decade of growth after the 2008 recession and during the Eurozone crisis, when contractionary austerity measures and nearly deflationary monetary policy were imposed on it at the behest of fiscal scolds in Germany. The resulting stagnation and underinvestment contributed to the rise of populism, the next crisis to batter Europe. Coronavirus and the Ukraine War proved to be enough to shock Brussels into supporting a preliminary and provisional common debt instrument, which is laudable. But the need for solidarity is even greater now.

Sources:

Adler, David, and Jerome Roos. 2020. “If Coronavirus Sinks the Eurozone, the 'Frugal Four' Will Be to Blame.” The Guardian, March 31, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/mar/31/solidarity-members-eurozone-coronavirus-dutch-coronabond.

Algan, Yann, Sergei Guriev, Elias Papaioannou, and Evgenia Passari. 2017. “The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall): 309–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90019460?seq=1.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Ángel Ubide. 2025. “Now Is the Time for Eurobonds: A Specific Proposal.” Realtime Economics (blog). Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 30, 2025. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/now-time-eurobonds-specific-proposal.

Fatás, Antonio, and Lawrence H. Summers. 2018. “The Permanent Effects of Fiscal Consolidations.” Journal of International Economics 112 (May): 238–50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022199617301411?via%3Dihub.

Krugman, Paul. 2016. “When Europe Stumbled.” The Conscience of a Liberal (blog). New York Times, April 30, 2016. https://archive.nytimes.com/krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/04/30/when-europe-stumbled/.

Smialek, Jeanna, and Amelia Nierenberg. 2024. “European Troops Deploy to Greenland as NATO Defies Trump’s Arctic Threats.” New York Times, January 20, 2026. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/20/world/europe/europe-troops-greenland-trump.html.

Sonno, Tommaso, Helios Herrera, Massimo Morelli, and Luigi Guiso. 2018. “The Populism Backlash: an Economically Driven Backlash.” VoxEU, CEPR, May 18, 2018. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/populism-backlash-economically-driven-backlash.

Sorgi, Gregorio and Bjarke Smith-Meyer. 2025. “EU to Pay €3B Interest Per Year on Ukraine Loan.” Politico, December 19, 2025. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-to-pay-e3b-interest-per-year-ukraine-loan/.