Not All Sectors are Created Equal: Corporate Tax Discrimination in Canada’s 2025 Federal Budget

This year’s federal budget announced the laudable goal of reducing Canada’s rates of capital taxation in an effort to attract investment and reverse Canada’s stagnant productivity per worker. Yet the budget has ignored an important flaw in Canada’s current system of capital taxation: tax discrimination. Tax discrimination is when the tax system treats similar tax payers differently without sound moral or economic justification. Tax discrimination is not only morally wrong, it is costly. In the case of capital taxation, tax discrimination causes capital to seek lower tax rates rather than higher returns. It lowers tax revenues and causes misallocation by shifting investments from more to less productive sectors. As will be outlined later in this article, Canada suffers from high levels of capital tax discrimination and it has cost the nation dearly. Unfortunately, this year’s budget takes tax discrimination to new heights.

The federal government’s preferred measurement of capital taxation is the average marginal effective tax rate or AMETR. The AMETR tries to estimate the government’s total tax take on investment returns. Budget 2025 announced a headline reduction in the AMETR from 15.6% to 13.2%. However, a peer review by Jack Mintz, a leading Canadian expert on METRs, yielded a different result. Mintz noted that the federal government’s calculation omitted key taxes and certain sectors of the economy. The inclusion of these variables changes the headline reduction of the AMETR to 15.8% from 18.8%. Most relevant to this analysis, the headline reduction in AMETR hides the fact that Canada’s system of capital taxation discriminates wildly between sectors.

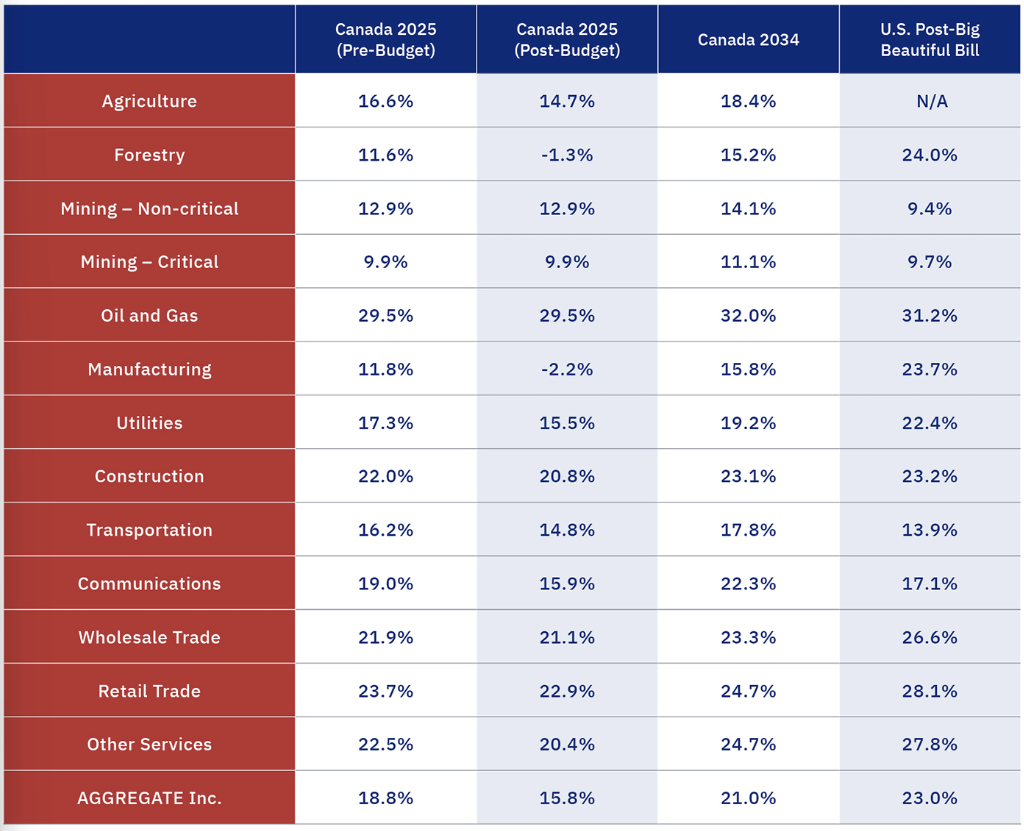

Figure 1: Sectoral METRs in budget 2025 as calculated by Jack Mintz.

As displayed in figure 1, budget 2025 widens sectoral tax discrimination in Canada. The most taxed sector, oil and gas, faces an METR of 29.5% while the least taxed sector, manufacturing, faces an METR of -2.2%, a difference of over 30%. Gaps in the treatment of capital taxation in Canada arise from taxes levied at multiple levels of government, not just the federal level. Yet, the fact that the 2025 budget widens the gap between these two industries by more than 10% highlights the role that this budget is playing in worsening Canada’s tax landscape. Moreover, this pattern is repeated over multiple sectors, not merely manufacturing.

1. Misallocation

In a healthy market, capital should flow to the places where it will be most productive. Such an arrangement redounds to the benefit of all parties: it helps workers, by giving them jobs, boosting their productivity, and ultimately raising their wages; it helps investors, by giving them the largest possible returns; and it helps the government, by generating more tax revenue. This scenario is encouraged by a neutral system of capital taxation where capital is treated equally regardless of its destination.

This will not be the outcome of budget 2025. Under these rates, capital will flow to the sectors with the lowest METR and not those most in need. The results of this inevitable tax avoidance will be lower productivity growth, smaller gains for workers and investors alike, and lower government revenues.

It should be noted that the sectors receiving the harshest treatment in budget 2025: oil and gas, retail trade, wholesale trade, other services, construction and utilities are those which have seen the greatest productivity gains in the last decade as per Statistics Canada. Meanwhile, the sectors receiving the most generous tax treatment such as manufacturing and forestry are those who have actually become less productive in recent years. Such patterns beg the question whether the cuts to the taxation of capital in budget 2025 were made in the majoritarian interest of most Canadians or the minoritarian interests of certain well-connected sectors.

2. Regional Inequalities

Canada is the world’s second largest country by land area with different industries inhabiting different provinces. Budget 2025 risks discriminating not only between industries but between provinces and exacerbating regional divisions as a consequence. The winners in this budget are British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario. Favoured industries such as manufacturing, forestry and mining are heavily concentrated in these provinces. The losers are Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Disfavoured industries such as oil and gas, retail trade, wholesale trade and construction are concentrated in these provinces. At a time where Canadian national unity is shaky, tax discrimination between provinces may present political, not merely economic risks.

3. Negative Marginal Rates of Taxation

Economists vary widely in their estimates of the optimal METR on capital investments; yet practically none of them would endorse a negative one. A negative METR implies that if an investor earns $1 by investing in Canadian manufacturing, the government will give them ¢2.2 of additional profit. This arrangement is now law in Canada. Beyond the obvious mistake of governments handing out tax payer money to shareholders, negative marginal rates of capital taxation risk encouraging “fake investments” where corporations game the tax system in order to receive large subsidies without making any changes to their behaviour. While this may sound like a hypothetical, this behaviour is strikingly common in countries with large investment subsidies of which Canada is now one.

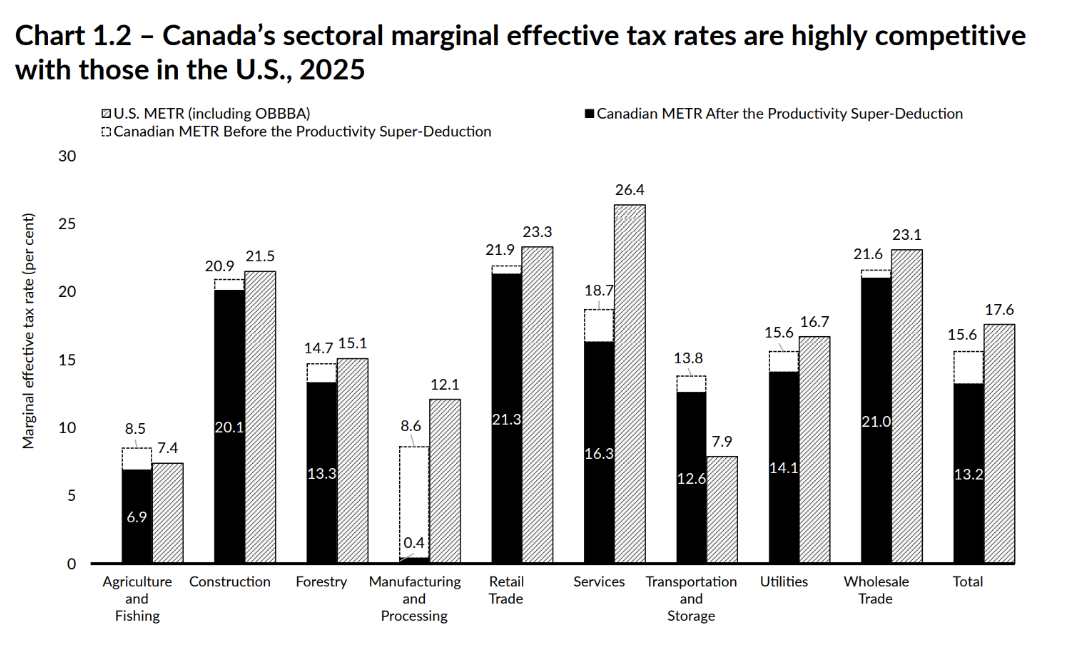

What is perhaps most worrying about the negative METRs on capital presented in budget 2025 is that in the budget’s official presentation the federal government appeared to be unaware that the sum total of their interventions were negative METRs in certain sectors. As seen in Figure 2, the federal government’s estimates of sectoral METRs differ significantly from Mintz’s peer review. This is not wholly surprising. METR is a notoriously difficult metric to calculate given the complexity of the tax code. Yet rather than exonerating budget 2025 its complexity opens up an entirely new line of criticism: that the federal government has produced a budget so complicated that the federal government itself does not fully understand it.

Figure 2: Sectoral METRs as presented in the budget.

Ultimately, it is imperative that Canada end its chronic problem with tax discrimination and work towards a system of neutral taxation that redounds to the benefit of all Canadians. A neutral tax code would not only make Canada more tax-competitive, it would smooth regional divisions and be easier to administer.

References

Canada. 2025. Budget 2025: Canada Strong — Our Plan: Building, Protecting, and Empowering Canada. Ottawa: Department of Finance. November 4. https://budget.canada.ca/2025/report-rapport/pdf/budget-2025.pdf.

Mintz, Jack. 2025. “Canada is not as tax competitive as the Carney government claims.” The Hub (via Macdonald-Laurier Institute). November 19. https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/canada-is-not-as-tax-competitive-as-the-carney-government-claims-jack-mintz-in-the-hub/.

Mirrlees, James A. 2011. “Dimensions of Tax Design.” In Tax by Design: The Mirrlees Review, edited by James A. Mirrlees, Stuart Adam, Timothy Besley, Richard Blundell, Stephen Bond, Robert Chote, Malcolm Gammie, Paul Johnson, Gareth Myles, and James Poterba, 1–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Statistics Canada. 2025. “Indexes of labour productivity and related measures, by business-sector industry (seasonally adjusted), Table 36-10-0207-01.” Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610020701&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.1&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.start