Involution and Overcapacity in China: Why Policy Fixes Fall Short

A new term has entered the lexicon of Chinese economic analysis: involution. In Chinese, this term translates to “nei-juan”, a concept that refers to a state of “excessive and self-defeating competition among Chinese companies for limited resources and opportunities”. In this situation, intensifying effort yields diminishing returns for all participants (Lo, 2025). This phenomenon is best captured with a theatre metaphor: in a crowded theatre, one person stands to get a better view, forcing everyone else to stand as well. Ultimately, no one’s view improves, but all are exhausted from the extra effort (Wieviorka, 2025).

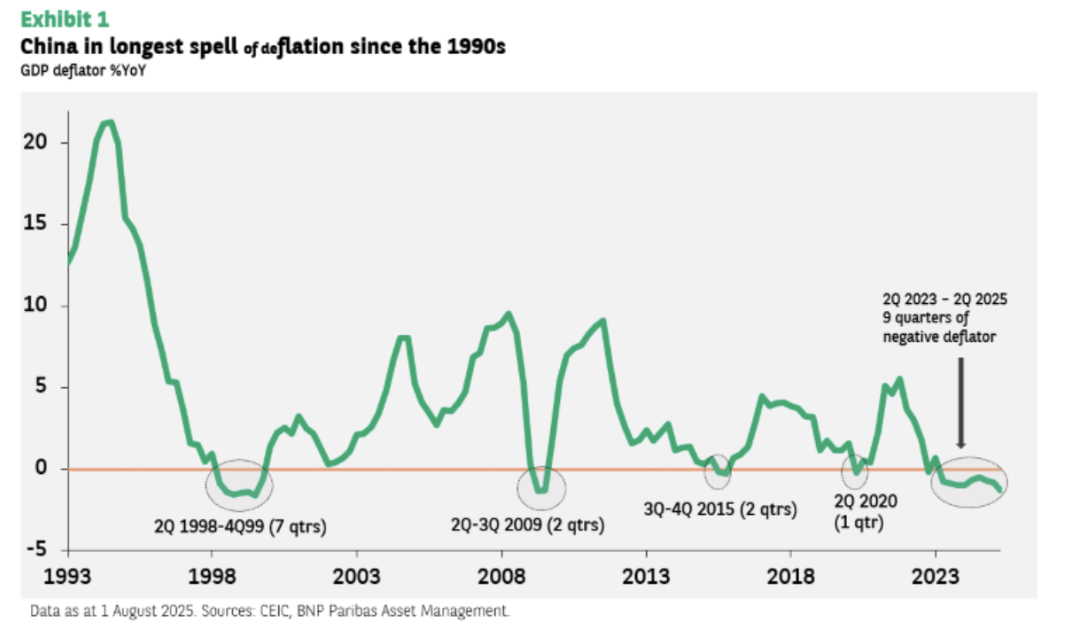

This dynamic is crucial to understanding the current policies and economic challenges China is facing. The current anti-involution plan the Chinese government is pursuing focuses on resolving the supply and demand imbalance by concentrating on specific-sector issues. However, the country is in its longest and deepest period of deflation since the 1990s, which signals a structural malaise (Lo, 2025; Wieviorka, 2025).

China’s involution issue is not a temporary market failure, but a structural outcome. Indeed, the country’s entrenched supply-side, investment-driven model systematically suppresses household income to subsidize production and leads to chronic overcapacity and destructive competition. While Beijing's recent "anti-involution" campaign addresses the symptoms through administrative fiat, it must also consider deeper reforms. A sustainable solution is impossible without a paradigm shift away from investment-led growth and towards a rebalanced economy empowered by domestic demand (Wieviorka, 2025).

Although involution has deep roots, its current severity was triggered by a series of policy decisions and economic shocks after 2020. The crisis emerged not by accident but as a direct consequence of Beijing's strategic response to a slowing economy. To attain GDP goals, the Chinese government focuses on an investment-driven, supply-side growth model that prioritizes production over domestic consumption.

The trigger was the collapse of China’s real estate sector in 2021–2022. As property developers cut investment sharply, Beijing faced a serious threat to GDP growth. Because the growth model could not tolerate a decline in investment, the state redirected capital away from real estate and toward manufacturing (Pettis, 2025). This shift was politically necessary to stabilize headline growth, but it was not driven by market demand.

This redirection of capital followed the framework laid out in the 2020 “dual circulation” strategy. The policy identified sectors such as electric vehicles, lithium batteries, solar energy, and advanced manufacturing as national priorities (Lo, 2025; Wieviorka, 2025). These industries, often referred to as the “new three”, became the main recipients of state-directed investment (Pettis, 2025).

Central priorities caused intense local competition. Provincial and municipal governments, under pressure to meet growth targets, offered subsidies, cheap land, tax exemptions, and financing to attract investment (Wieviorka, 2025). This led to duplicated projects and rapid oversupply. Crucially, weak bankruptcy enforcement and high exit barriers prevented failing firms from leaving the market. Local governments often protected unprofitable “champion” firms to preserve employment and tax revenue (Wieviorka, 2025).

To add pressure on the situation, the surge in supply collided with structurally weak demand. Consumer confidence deteriorated after 2020 due to job insecurity, falling property values, and rising precautionary savings (Wieviorka, 2025). Household income growth has lagged behind production, and the erosion of household wealth after the property crash has reinforced saving over spending (Wieviorka, 2025). The same growth model that fuels overcapacity also depresses consumption by transferring income from households to producers. A limited social safety net further encourages precautionary saving, reducing the effectiveness of short-term consumption subsidies.

These factors combined to create a perfect storm, channelling state-directed investment into a narrow set of industries just as the domestic economy was weakening. The resulting dynamic of oversupply and under-consumption has had tangible and damaging consequences across the economy. It unleashed a destructive price war where companies cut prices to survive in the market. Since early 2023, leading EV makers began cutting prices to gain market share, and competitors were forced to cut prices just to survive, often at the cost of all profitability. For example, the BYD Seagull car can be bought for just $7800 and the company. In 2024, BYD had overtaken its competitor, SAIC, and became China’s best-selling carmaker. Nevertheless, BYD’s market share was only 15% in that year, nowhere near SAIC’s 25% market share when it led the market in the 2010s. (Xiong, 2025)

This resulted in China entering its longest deflationary period since the 1990s (Lo, 2025). The GDP deflator has fallen for nine consecutive quarters, reflecting economy-wide excess capacity (Wieviorka, 2025). In industries such as EVs, solar panels, and e-commerce, firms have repeatedly cut prices, often below cost, simply to maintain market share and reduce inventories. This competition has devastated profitability. In the automotive sector, total profits fell by 33% between 2017 and 2024, even as sales rose by 21% (Wieviorka, 2025). With more production and effort producing lower returns, this is a textbook case of involution.

The polysilicon industry, a key upstream input for solar panel manufacturing, illustrates the scale of the problem. After the property collapse, in less than four years, the top four Chinese producers managed to add the capacity equal to two-thirds of the total global capacity (Pettis, 2025). It puts China as world-leading in the industry, supplying about 95% of the world’s polysilicon supply. The problem is that this is roughly double the global demand. This overload of supply drove capacity utilization below 40% in 2025, forcing producers to sell panels at prices below their variable costs (Pettis, 2025).

It should be noted, however, that although neijuan is a new term, the underlying problem is not. China has faced similar overcapacity crises before, most notably during the 2015–2016 supply-side reforms, but also in the State-Owned Enterprises layoffs of the late 1990s (Xiong, 2025). However, the current episode is more difficult to resolve; China cannot stick to the same solutions anymore. Unlike earlier reforms that targeted state-owned heavy industry, today’s overcapacity is concentrated in newer, downstream sectors dominated by private firms (Xiong, 2025). Much of the capacity is also newly built and not yet depreciated, making closures politically and financially costly (Wieviorka, 2025).

Beijing’s “anti-involution” campaign represents a serious attempt to curb the most damaging effects of excessive competition. Measures include revisions to the Pricing Law, coordinated production cuts, and sector-specific interventions such as plans to retire excess polysilicon capacity (Xiong, 2025). However, these policies treat the symptoms rather than the cause. They reduce capacity in one sector without changing growth incentives, simply shifting overinvestment elsewhere. Indeed, while investment slows in EVs and solar, capacity expansion is accelerating in petrochemicals, another sector already facing involution (Pettis, 2025).

A lasting solution requires a deeper transformation of China’s growth model and, especially, the breaking of local protectionism (Xiong, 2025). Two reforms are essential: strengthening domestic demand and accepting lower investment-led growth. Indeed, the supply-side reforms must be paired with strong fiscal support for households. In a liquidity-trap environment, fiscal policy, not monetary easing, must play the central role in restoring confidence and consumption (Lo, 2025). In parallel, China must reduce its reliance on manufacturing and infrastructure as primary growth engines. This would require Xi Jinping to confront an uncomfortable political trade-off: accepting lower GDP growth targets in order to pivot the economy toward services, consumption, and household income growth (Wieviorka, 2025).

The release of China’s next five-year plan in March 2026 will be a critical test (Wieviorka, 2025). It will reveal whether Beijing is prepared to confront the structural roots of involution, or whether it will continue to manage the symptoms while the underlying cycle of overcapacity, deflation, and waste persists.

Sources:

Pettis, M. (2025, August 26). What’s New about Involution? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/08/whats-new-about-involution?lang=en

Wieviorka, S (2025, October 2). China: Behind involution lie deep-seated economic imbalances. Crédit Agricole Group. https://www.credit-agricole.com/en/news-channels/the-channels/economic-trends/china-behind-involution-lie-deep-seated-economic-imbalances

Lo, C. (2025, November 8). China: Involution, deflation and structural reform. BNP Paribas Viewpoint. https://viewpoint.bnpparibas-am.com/china-involution-deflation-and-structural-reform/

Xiong, Y. (2025, September 17). Understanding China’s “anti-involution” drive. Deutsche Bank. https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RI-PROD/PDFVIEWER.calias?pdfViewerPdfUrl=PROD0000000000603307&rwnode=REPORT